The Jigsaw Method: Making the Pieces Fit

An active learning strategy where every student is responsible for teaching and learning

by Ian Jobe, PGY1 Pharmacy Practice Resident, Magnolia Regional Health Center

Since the dawn of universities, lecture-based instruction has been the backbone of education. Traditional lectures remain the quintessential teaching method in higher education today. Even though universities may be steeped in tradition, we educators should ask ourselves if this method is truly the best way to teach learners for every lesson. One meta-analysis from 2014 showed that active learning could increase exam performance by nearly half a standard deviation and that lecture-based teaching resulted in a failure rate 1.5 times greater than instruction that included active learning strategies.1 If active learning methods are more effective, the next question is, “What active teaching methods should we pursue?”

The Jigsaw Method is a type of cooperative learning technique created in the 1970s by Dr. Elliot Aronson during his tenure at the University of Texas.2 Reminiscent of Henry Ford’s seminal creation, the moving assembly line, the Jigsaw Method requires each student to specialize in one specific aspect of a topic, lesson, or project. The central philosophy of the method is to make each student essential in the classroom.

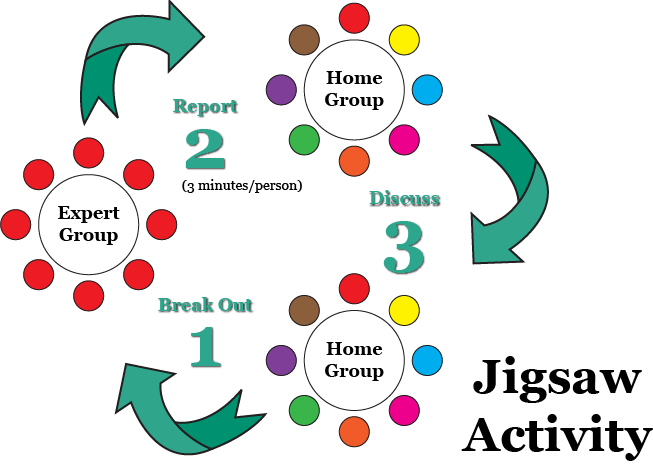

The method begins by dividing students into groups of 5 or 6 with a designated leader. As much as possible, each group should be diverse, based on the classroom’s gender and ethnic demographics. The lesson/subject should be split into 5-6 pieces and each member of the group is required to familiarize and understand an assigned element. After adequate preparation time, students move into an “expert group,” where they discuss their assigned element of the project/lesson with other students assigned the same element of the topic, thus allowing each student to expound on what they have learned about their assigned element of the topic. The students then return to their original group, and each student then presents what they have learned from their “expert group.” If there is turmoil within the group, the group leader can be trained on how to appropriately intervene to avoid having a member derail or dominate the discussion. At the lesson’s conclusion, all students are held accountable for knowing the entire topic through either a quiz or test. In theory, the Jigsaw Method sounds like a potentially useful learning strategy, but how does it fare in practice?

One study from Iran in 2017 compared conventional lecture-based teaching to the jigsaw method for a physics course at the Gonabad University of Medical Sciences.3 Thirty-four students were given a pretest on electricity to establish baseline knowledge. The students were then split into two groups, where one group received lectures about bioelectricity while the other used the Jigsaw method to learn about bioelectricity. The groups then swapped instructional methods to learn about a second subject, the application of electricity for diagnosis and treatment. The only major demographic difference between the two groups was their mean age (21 years old vs. 26 years old). The pretest scores for the two groups were nearly identical, but post-test scores painted a much different picture. The results of the study showed that both groups excelled when the jigsaw technique was used when compared to the group that learned the material from an instructor-delivered lecture — the mean score was at least 3 points higher. When surveyed, 94% of the students agreed that the jigsaw technique helped them retain the material. The authors concluded that the jigsaw method, through its cooperative principles, is superior. One conclusion that could be drawn in favor of the jigsaw method from this study is that it increases engagement, which could help boost the students’ interest in the subject matter. It is worth noting that the experiment occurred with a rather small sample size and was conducted in a science course (physics), and not an applied science course like healthcare. So, does research show any benefit for healthcare workers?

One study conducted at Stony Brook University Hospital in Suffolk County, New York put the Jigsaw Method to the test.4 Over three months, 51 PGY1 and PGY2 medical residents were involved in a patient safety workshop. Twenty participants were taught using a traditional small group method while 31 participants learned the material using the Jigsaw method. The residents were given a one-page paper detailing a diagnostic error and were tasked with piecing together the segments to solve the case’s outcome. The traditional small group was required to understand the paper as a whole within their group, while the jigsaw method groups broke down the paper into components, which were then assigned to a member of the group. The “expert groups” would gather to discuss their assigned component. After discussions, both groups were given a quiz to complete. The results of the study showed that the average mean test score for the traditional small groups was 70.5 but was 84.5 for the participants in the Jigsaw groups. The residents took a follow-up test one year later, and the mean score was 65 in those who received traditional instruction but was 80.7 in the group that learned the material using the Jigsaw Method. This study, albeit small, showed that in this group of medical residents, the jigsaw method was superior to traditional instructional methods. Furthermore, the Jigsaw Method resulted in greater long-term retention.

As documented in these studies, the Jigsaw Method may result in enhanced learning and knowledge retention when compared to lecture-based instruction, perhaps due to increased student interest and engagement. Furthermore, it shows promise over traditional small group discussions by allowing students to learn from each other. For healthcare education, I can see there being much benefit in using the Jigsaw method to prepare students for interdisciplinary teams. In hospitals across the United States, teams made up of physicians, pharmacists, nurses, social workers, dieticians, physical therapists, and others participate in discussions to further their understanding of the best approach to care for patients. As healthcare workers, they each have their own specialized knowledge that is brought to the table. During patient care rounds, each individual is required to explain their plan and recommendations for the patient. The Jigsaw Method could easily be used for interprofessional education (IPE) before a student enters advanced practice experiences or the workforce.

The Jigsaw Method seeks to hone learners' specializations and increase their value in group discussions. Studies have shown that the method not only increases group engagement and boosts test scores but may also enhance long-term retention of the material discussed. Instructors may find this instructional strategy very useful for workshops involving interprofessional learning. While lecture-based teaching may still be the standard in healthcare education, the Jigsaw Method might help make all the pieces fit.

References:

Freeman S, Eddy SL, McDonough M, et al. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111(23):8410-5.

Aronson, Elliot. The Jigsaw Classroom [Internet]. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Social Psychology Network; 2000. [Revised 2014, Cited 1/3/2024].

Jafaivan M, Esmaelili R, Kianmehr M. Effectiveness of teaching: Jigsaw technique vs. lecture for medical students’ Physics course. Bali Med J 2017; 6 (3): 529-533.

Goolsarran N, Hamo CE, Lu WH. Using the jigsaw technique to teach patient safety. Med Educ Online 2020 Dec;25(1):1710325.